Mental health and well-being

Introduction

We are aware and completely understand that working in academia can have a significant negative impact on mental health and well-being. Several members of staff at UKRIO were previously researchers and know first-hand the challenges that impacted our personal lives and well-being during that time and even sometime thereafter. Like many specialist careers, being a researcher often becomes more than a job: it becomes an identity. You may feel you are at a crossroads, at the start of the decision-making process to leave academia, or you may be experiencing difficulties as a PhD student, or in your first post-doctoral position or senior role.

An individual researcher cannot change the current research system and the main stressful concern is of a lack of job security. You may continue to feel you are sacrificing too much of your personal life and falling behind those who have already reached life milestones that seem out of reach to you, but what do you do about it? A simple answer is you can leave: leaving isn’t a failure, it is simply an opportunity, though the journey of leaving can itself be mentally draining.

This resources page can’t give you the answers on how to be a happy researcher and stay in research nor how to leave, but it can be reassuring to read that other researchers are also experiencing struggles both in mental health and well-being.

It’s important to acknowledge that mental health challenges in research are not unique, and seeking help and support is a sign of strength, not weakness. Universities and research organisations are increasingly recognising the importance of addressing mental health issues, and efforts are being made to create more supportive and sustainable research environments.

Good mental health, like all things, takes practice and maintenance. Take a deep dive into your own mental health and acknowledge how you respond to being a researcher. How do you react to colleagues, how do you respond to a disappointing review or a failed theory? Remember that managing stress and mental health is a lifelong journey, and it’s entirely normal to experience stress in different phases of life. Being proactive about self-care, seeking help when needed, and building a strong support system can contribute to a healthier and more resilient mindset, both during and after academia.

This resources page is a collection of signposted materials to help you explore and evaluate, complementing our resources on Equality, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

Long-term mental health impact of working in academia

Academic experiences, such as intense workloads, competition, and perfectionism, can have a lasting impact on mental health. It’s essential to acknowledge and address these effects and seek professional help if needed.

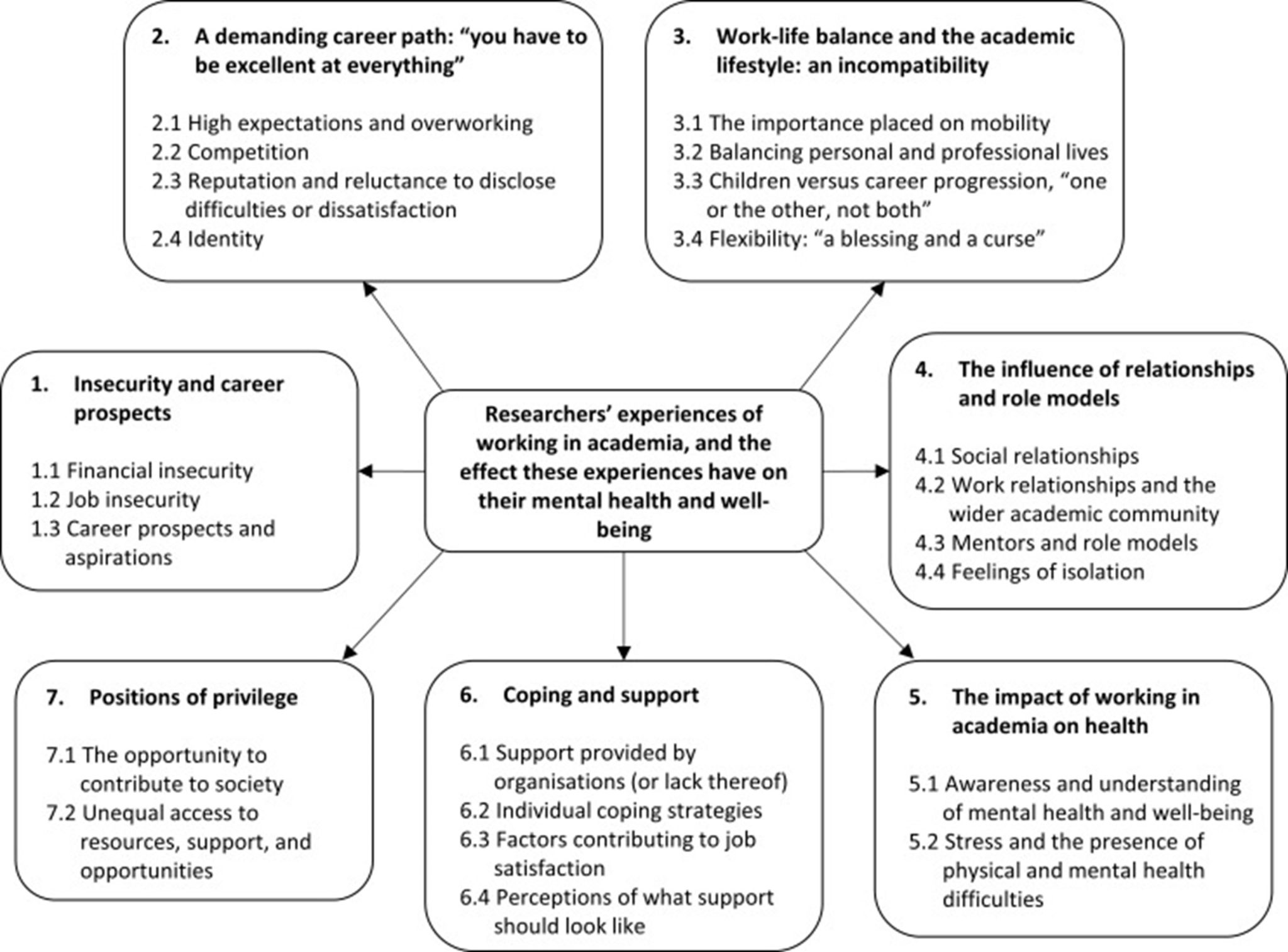

A visual representation of the main themes and sub-themes identified through the meta-synthesis.

Image taken from Fig. 2 in Nicholls, H., Nicholls, M., Tekin, S., Lamb, D., & Billings, J. (2022). The impact of working in academia on researchers’ mental health and well-being: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. PLOS ONE 17(5):e0268890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268890. CC-BY 4.0.

- Mental Health in Academia, eLife. A collection of articles that explore mental health in academia from PIs, ECRs, to non-academic staff.

- Páramo, B.G. (2020). Why are we talking about the mental health of researchers? Society of Spanish Researchers in the United Kingdom.

- Why research culture matters: Limas, J.C., Corcoran, L.C., Baker, A.N., Cartaya, A.E., & Ayres, Z.J. (2022). The Impact of Research Culture on Mental Health & Diversity in STEM. Chem. Eur. J., 28, e202102957. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202102957

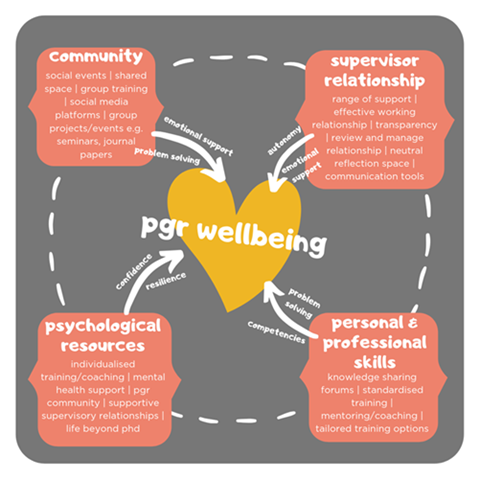

What can universities do to support the well-being and mental health of postgraduate researchers?, a blog post based on this paper:

Watson, D., & Turnpenny, J. (2022). Interventions, practices and institutional arrangements for supporting PGR mental health and wellbeing: reviewing effectiveness and addressing barriers. Studies in Higher Education, 47:9, 1957-1979, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2021.2020744

Image to the right by Tarnia Mears (UEA), taken from above article, Fig. 2. Approaches to enhancing PGR wellbeing, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

Trying things differently: Kindness in Science

From Boulter, J., Orozco Morales, M.L., Principe, N., & Tilsed, C.M. (2023). What is Kindness in Science and why does it matter? Immunol. Cell Biol., 101: 97-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/imcb.12580

Image taken from above paper, Fig. 2: Kindness in Science pillars include the following: kindness to the community, kindness to ourselves, kindness to the environment and kindness to other scientists. CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The impact of leaving academia

Transition stress: Leaving academia, whether by choice or due to circumstances, can be a major life transition. This transition can be stressful, as individuals may face uncertainties about their career path, identity, and financial stability. The academic community often provides a strong social support system. Leaving academia can mean losing that support network, which can lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Recovery and adjustment: Transitioning out of academia can take time, and individuals may need time to recover from the stresses and pressures they experienced during their academic careers. Adjusting to a different work environment or lifestyle can be challenging.

Psychological effects: Academic experiences, such as imposter syndrome, anxiety, or depression, can leave lasting psychological effects. These issues may continue to affect individuals even after they’ve left research.

- Minimising the trauma of leaving academia, UCL Researchers, 2019

- Careers case studies, UCL Researchers

- “Science in Motion: Navigating Transitions” – Winner of the 2023 EACR Science Communication Prize, The Cancer Researcher

- The Professor Is Out, Facebook Group

What you can do for yourself

Regular check-ins: Periodically assess your mental well-being, even if you believe you’ve left the primary sources of stress behind. Mental health is an ongoing process, and it’s essential to address issues as they arise. Simply ask yourself: How am I feeling? Why am I feeling that way? Having a lack of self-awareness or understanding of one’s own needs, limits, and well-being can lead to behaviours and decisions that are not in line with your genuine needs and desires. It can result in stress, dissatisfaction, and an unbalanced life.

Resilience and coping: Developing resilience and coping strategies can be useful in managing stress. These skills can help individuals navigate challenges in their personal and professional lives but at certain times may not always be available to the individual. Although resilience can be helpful, be mindful of continuously putting on a brave face as this may exhaust your inner strength and continue you on a path to an unrealistic or unattainable goal. Work stressors that are continuous and unmanaged cannot be rectified by resilience alone. Forcing yourself to be more resilient can mask the severity of a situation that is beyond your control and make you feel like you are not good enough. It is important to scrutinise stressors and regulate being overburdened.

- Osborne, N.J. (2023). Is mindset awareness the key to unlocking your research potential?Laboratory Animals, 57(2): 127–135

- This webinar also gives some useful background and context to mindset awareness: https://www.responsibleresearchinpractice.co.uk/2023/07/18/is-mindset-awareness-helpful-in-research-cultures/

- Mental Health During Your PhD – The Cancer Researcher (eacr.org), 2019. Downloadable poster by Zoë Ayres.

- Be conscious of extreme resilience and being unrealistic: Resilience Institute | Are there Downsides to Resilience?

- There can be barriers to resilience: Managing stress and building resilience – tips – Mind

Support networks: Building and maintaining a strong support network of friends, family, mentor and potentially therapy or counselling can provide valuable assistance in managing stress and maintaining mental well-being. Look for institutional support available to you for not only mental health and well-being but for mentoring schemes.

Networks to try:

Work-life balance: Striking a healthy work-life balance remains crucial, regardless of one’s career path. Managing stress often involves setting boundaries and prioritising self-care.

Ideas for self-care:

- What does self-care mean to you? Healthcare science self-care handbook, NHS England, 2022

- El-Ghoroury, N.H. (2015). Self-care for the scientist. gradPsych Magazine, APA

Professional help: If stress and mental health concerns persist, don’t hesitate to seek professional help from therapists, counsellors, or psychiatrists. They can provide guidance and support tailored to your specific needs.

Try out skills such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT): Self-help CBT techniques, Every Mind Matters – NHS

Remember that managing stress and mental health is a lifelong journey, and it’s entirely normal to experience stress in different phases of life. Being proactive about self-care, seeking help when needed, and building a strong support system can contribute to a healthier and more resilient mindset, both during and after academia.

Last updated October 2024

Please note that this list of resources is not intended to be exhaustive and should not be seen as a substitute for advice from suitably qualified persons. UKRIO is not responsible for the content of external websites linked to from this page. If you would like to seek advice from UKRIO, information on our role and remit and on how to contact us is available here.