Trends in UK Research Integrity – a decade of change?

Ian L Boyd, Chair, UKRIO

The great yellow bumble bee, one of the rarest bees in the UK. Research on pollinators is susceptible to confirmation bias. Photo:IL Boyd

It is hard to open the pages of Science or Nature these days without seeing an article about an issue concerning research integrity. Anybody naively looking in on this could be forgiven for imagining there was a crisis in the quality of research, but I suggest what is happening is an essential evolution in scientific rigour.

I am the Chair of the UK Research Integrity Office (UKRIO) and, while this role is mainly about overseeing the strategy and performance of UKRIO as an organisation, it provides me with a ringside seat on the issue of research integrity.

After leaving Defra, where I was Chief Scientific Adviser, I was keen to take on the role of chairing UKRIO because I cared about what I had experienced in government. As a research scientist myself, I had been forced to look back at the research community I was part of – a sensation not unlike an astronaut looking back at Earth – and too often what I saw was problematic.

I was often deeply worried by the quality of the research available to support government decisions. In contested fields from the culling of badgers to air quality, declines in pollinators, the effects of pesticides, and plastics in the environment, and many others, it was often hard to get a clear sense that the messages being produced were robust.

Of course, uncertainty is all a part of science, and those people who think that all published research should be correct misunderstand the scientific process. My worry was, however, that many researchers were starting from a fundamental misunderstanding of the philosophical basis of their methods.

For example, in the case of the effects of plastics in the ocean I sensed that the task that many researchers had set themselves was to search for effects until they were found rather than rigorously testing whether any of those effects were important or real. The social amplification overlying research, often caused by the claims of importance made by researchers themselves, makes it is all too easy for results with weak statistical support to become truths. These are subtle effects which the philosopher Mary Midgley referred to as “think[ing] about the right way to think”. She also summarised the problem as “Ask not ‘whether’ but ‘how’?”. It is my view that the incentives for scientists channels their thinking down narrow routes. When this occurs systemically across whole fields of science, which could be more the norm than the extreme these days, it becomes hard to believe a lot of what is published.

I could, perhaps, be accused of unnecessarily extreme scepticism, but this experience arose in parallel with what could be described as the replication crisis – the realisation that across many fields there was apparently settled science which was being questioned because other researchers could not replicate the results.

These discoveries were accompanied by doubts about how clinical trials in particular were being conducted because of the ways in which negative results would go undeclared or about how study designs could be hedged towards achieving certain outcomes. I also saw the ugly image of confirmation bias written all over many of the fields of research I was having to take an interest in.

Researchers are people with all the weaknesses associated with human frailty. Where there are incentives to behave in certain ways then people will follow, and this includes researchers. Much has already been written about the perverse incentives associated with the publish or perish culture but incentives to stretch the boundaries of the norms within research are very pervasive. No source of funding is unconnected with providing incentives for researchers to bias their studies. Everybody from funders to researchers themselves have interests, nobody is independent in spite of what they may claim. Some interests are more explicit than others and unconscious biases are the most dangerous.

For researchers, one of the most cathartic processes they could embark upon is challenging themselves about their own interests and, in the process, bring their biases to the surface. Researchers themselves have to question their own integrity and reflect on what good research practice means in terms of their own work. I suggest that those who find nothing to worry about have simply not delved deeply enough.

The focus of UKRIO is to help researchers to delve down deep and bring the issues to the surface, to openly challenge and critique them. It provides not only advice about how to address problems and misconduct, but acts as a guiding hand and resource for best practice. UKRIO aims to promote a healthy research culture/environment so that when mistakes happen, researchers are in a supported space to work through the issues and to improve the quality of their research. However, there is often no clear dividing line between what constitutes misconduct and poor practice. Misconduct is the emergent consequence of all the other things going on within the research community, the tip of the iceberg.

The data coming out of UKRIO may help us to understand the emerging picture of research integrity in the UK.

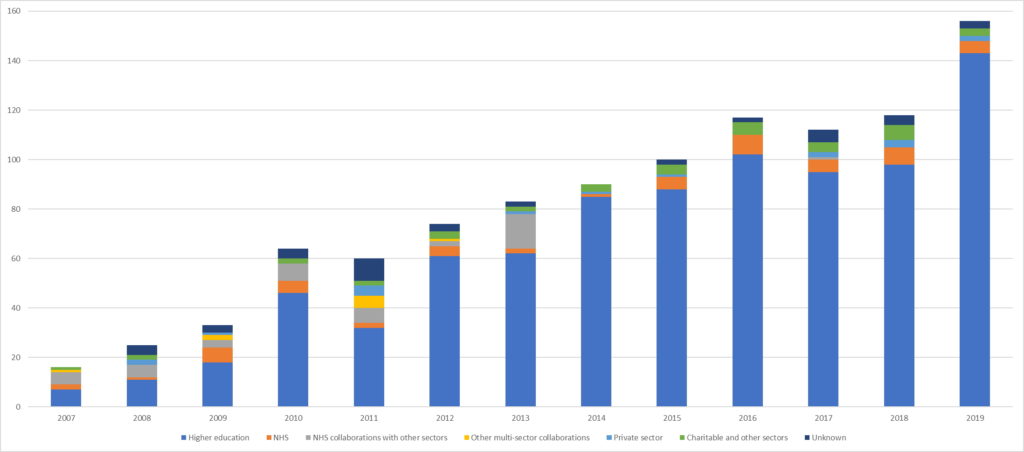

UKRIO has experienced a steady rise in the number of enquiries it has received (Figure 1). These are a mixture of informal requests for information and serious calls for help. In 2007 when UKRIO’s Advisory Service first came into existence it dealt with just 16 formal requests for assistance with integrity matters. In 2019 this had risen to 156 formal requests for help. There is no requirement on anybody to refer cases of research misconduct to UKRIO and not all of these enquiries are necessarily connected with misconduct, but there are perhaps some messages in this trend.

Figure 1. The number of formal requests to UKRIO for assistance from 2007 to 2019 (n=1048).

Most (71%) of the increase has been because of enquiries from institutions, and in 2019 the vast majority those institutions came from the higher education sector. Enquiries from most other sectors of the research community, including the NHS, have remained roughly stable and there have been virtually no enquiries from either the public or private sectors.

The number of enquiries coming from researchers themselves or members of the public has also remained fairly stable but is now a diminishing proportion of the total because of the rise in institutional enquiries. There has been a slight rise in enquiries from overseas, perhaps because the UK is seen as a place where good advice can be obtained, but this involves less than 10% of the cases which UKRIO dealt with in 2019.

Over time, about one-third of all enquiries have come from the health and biomedicine sector followed by a large proportion from multiple other disciplines. The next largest proportion (about 12%) has come from the social sciences. The greatest increase over time has been in the category of multiple disciplines (about 25% of all enquiries), which captures the broad range of science activities that cannot be easily categorised, and cross-disciplinary work by institutions to support good research practice.

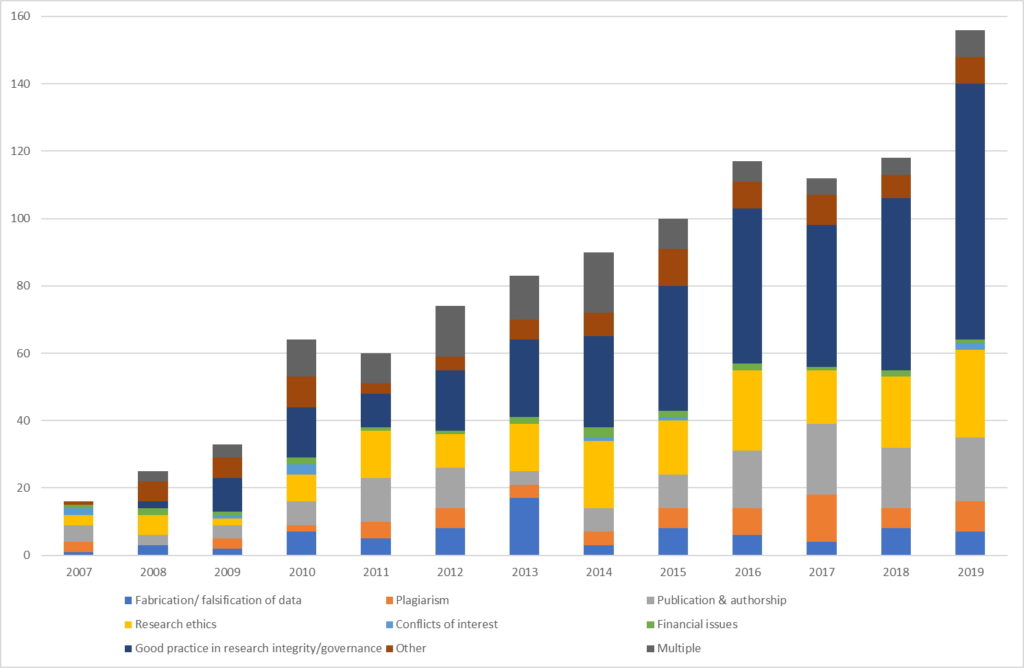

The reasons for referral tend to be very variable and they include plagiarism, falsification, research ethics, questions of publication ethics and authorship, financial mismanagement and conflicts of interest (Figure 2). However, the greatest increase in enquiries over time has been in the category of good practice and governance, which perhaps reflects the development of a deeper understanding that integrity is about more than just the most obviously dishonest practices.

Figure 2. The number of formal requests for assistance made to UKRIO by year and the type of integrity issue concerned (n=1048).

We should not see these statistics as a measure of the state of research integrity in the UK. These trends are almost certainly the result of changes in the appreciation of how important research integrity is for trust in research and, in particular, in the reputation of the institutions which pride themselves on having high ethical standards. The statistics mainly show that universities are increasing their vigilance and are increasingly responsive to issues as they arise.

However, there are some worrying gaps. For example, research institutions in government and the private sector remain a very small part of this emerging picture even though they have a major presence in the mix of research going on within the UK. This perhaps reflects awareness of UKRIO, but that in itself could be a reflection of awareness of the issue of research integrity across different parts of the research community.

Some fields of research also appear to be less represented than others. Again, it is not clear whether this reflects different levels of awareness of UKRIO, higher levels of research integrity, or lower appreciation of integrity as an issue in those fields.

These statistics are telling us that attitudes to research integrity in the UK are changing. At least in some sectors there is an increasing appreciation that there is a problem which needs to be dealt with through appropriate mechanisms of inquiry and accountability.

However, I do not think it tells us much about the level of research integrity in the UK or how it is changing. An assessment of that type would need a much more complex investigation.

UKRIO does not actively campaign for research integrity. Rather it is a practical resource to be used when people or institutions need its help. Therefore, it is unlikely that UKRIO itself can claim credit for the changes going on. These appear to be driven by the corporate responsibility of institutions, at least in some sectors.

My view is that the vast majority of researchers are deeply honest people who strive to project that honesty through their work. Sometimes, they are embedded in systems or cultures which push them, often imperceptibly, down routes where standards are allowed to slip. For those involved, this is often hard to detect – they find it tough to take the astronaut view of themselves – but there are messages from these data which suggest that some of the institutions they work for are doing more to help.

Professor Sir Ian Boyd FRSB FRSE, Chair, UK Research Integrity Office